The children’s books that explain social issues

Written by Portia Ladrido / Photos by Kenneth Aballa (CNN Philippines Life)

Manila (CNN Philippines Life) — It all started with a film. Gigo Alampay was a student at the University of the Philippines in the 1980s when he came across “The Man Who Planted Trees,” an animated film that was based on French author Jean Giono’s short story. It tells the tale of a man who plants trees over the course of 50 years. In the process, this fictional character transforms a barren landscape into a forest, and rebirths the land.

“It spoke to me about the power of an individual to make a difference by doing good for the sake of doing good,” Alampay says.

He went on to finish law school, left the country to take a graduate degree, and then returned to the Philippines after a few years. When he came back, the short film’s impact on him was still very much intact that he thought of creating an adaptation of the book for the Philippines.

While working on a USAID project that provides assistance for local governments on environmental matters, he started working on securing the rights of the book as a side project. He contacted Chelsea Green Publishing, the publisher of “The Man Who Planted Trees,” to ask how he could secure the rights of the book, and was pleasantly astonished by the editor’s response.

“The editor-in-chief then wrote me back, and said that he believes no one owns the rights to the book because Jean Giono had given it to the world for free,” Alampay recalls.

Still needing some sort of reassurance on intellectual property rights, he researched about other people who had attempted to secure the book’s rights as well. “I found this correspondence between Jean Giono and another person pero it was written in French,” he says. “I had a friend who was working in the UN and she spoke French tapos sabi niya ‘yun nga nakasulat dun na it's for everyone ... [Giono] doesn't earn a single cent from it because it's a gift to the world.”

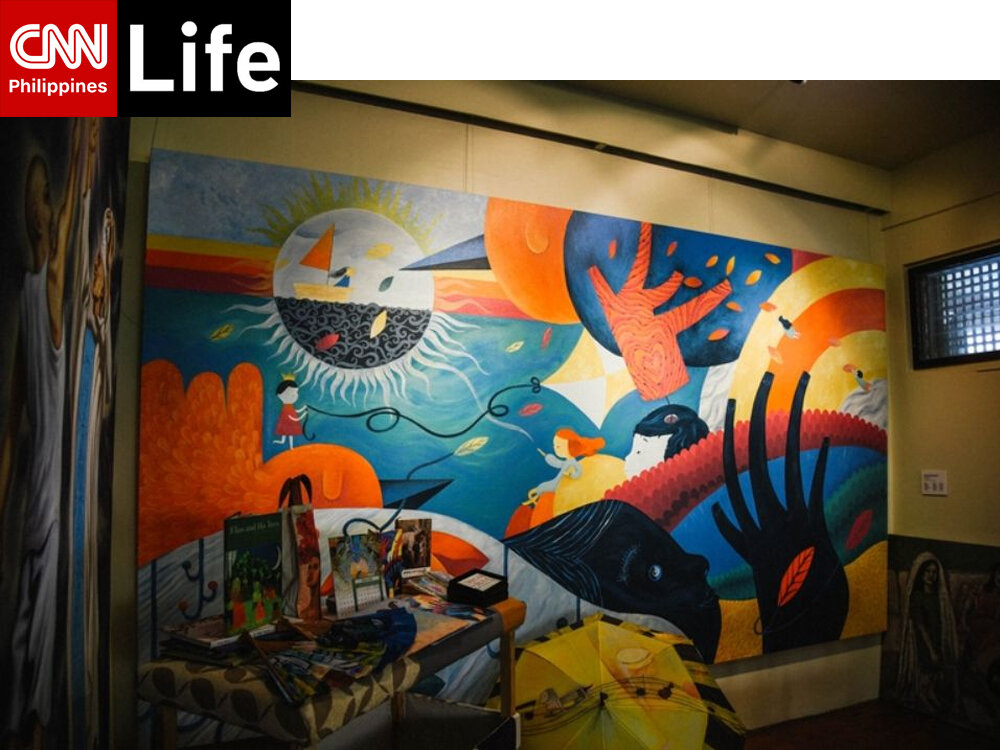

Alampay then got a grant from a California-based foundation to do the book. In 2004, he tapped Palanca-winning writer Augie Rivera to write an adaptation, and had artist Romeo Forbes create artworks for the book. A year later, Alampay launched the book titled “Elias and His Trees” while also selling the paintings that were from illustrations in the book.

Because of the commercial success of the book and the paintings, the grant he had received remained untouched. This enabled them to jumpstart a sustainable business model where they can publish more books, which led to the creation of the Center for Art, New Ventures, and Sustainable Development (CANVAS).

“It’s hard to publish books kasi it’s hard to sell books,” he says. “We found out that if we could find the right artists, we have a good chance of earning from the sale of paintings so that we can publish hardbound [books].”

A year after the launch, CANVAS started hosting their short story competition to continue publishing children’s books. First, the organization commissions an artist to create a painting or an illustration. They then release a painting on the internet, and Filipino writers who want to join the competition would then have to submit a children’s story based on the painting.

For their first competition, they had renowned contemporary painter Elmer Borlongan do about 20 artworks. “He was sought after by a growing number of collectors but more importantly, he was highly respected by the artists’ community. So our being able to get him gave CANVAS, which was then a one year old organization, instant credibility,” Alampay shares.

The paintings were sold out even before the exhibition opened, and the book, entitled “Rocking Horse” written by Palanca winner Becky Bravo, also won the Gintong Aklat Awards, a recognition given for outstanding publishers by the Book Development Association of the Philippines.

CANVAS has been running the competition for 12 years now, and would receive over 120 short story entries every time. While these recognitions are well and good, Alampay says that the mission of the organization has always been more than just publishing stories. In fact, the stories that he values the most are those that have a real, measurable impact on Filipinos and their respective communities.

He cites a short story illustrated by Liv Vinluan about a girl who's forced to flee her village because of war, and how this girl helps their entire village cope and recover from devastation. “That story is important to us kasi we were able to use that to help ‘yung mga children who were displaced by the conflict in Mindanao kasi there was a parallelism,” he shares.

Along with this book, CANVAS commissioned the Department of Psychology in Ateneo de Manila University to create a module about processing the trauma of displacement, which was then used by parents and teachers to help their children deal with their situation. This same module was later used for those who were displaced by Typhoon Haiyan.

“That story stands out for me kasi ‘yun nga, parang it's more of a demonstration of the power of books kasi you never know where it will lead,” he says. “In the same way na ‘yung kay Jean Giono, when he wrote that, surely, he could not have imagined na it will lead us to build this organization here.

CANVAS has also created activity books that tackle how children can care for the environment, as well as books that have narratives about human rights and freedom of expression, among others.

Their children’s books have reached various interest groups — from leftist groups and the military to individual students from universities and big organizations like Save the Children. And in 2013, they started the campaign called ‘One Million Books for One Million Children’ to all the more encourage organizations, corporations, and private individuals to help them give out books for free.

When asked about why he seems very determined to share as many books to as many Filipino children as possible, he starts citing statistics about the reality of the education system in the Philippines. “Fifty-five percent of children who enter elementary school will drop out. So most children will eventually drop out of school unless we're able to change the educational system,” he says. “The other statistic is we have a high literacy rate, maybe 95 or 96 percent in the Philippines. But statistics also show that a good proportion, up to 11 million of those, are functionally illiterate.”

This means that a substantial percentage of Filipino children either drop out of school or are able to read but cannot comprehend what they’re reading. “But if they love books, then they will really learn to read, and even if they drop out of school, statistics show, they likely will, they'll continue learning — that makes them more competitive, more productive, more broad thinking,” he explains.

Alampay says that their ‘One Million Books for One Million Children’ campaign seems like a long way to go, as they’ve only distributed 135,000 at the moment. But, with a subtle confidence and without the slightest bit of worry, Alampay adds, “Like ‘yung story nga dun sa ‘The Man Who Planted Trees,’ he just planted trees everyday and eventually he builds a forest, diba?”

“So I have no doubt that eventually we will reach one million. If we reach it in 10 years, 15 years, that's fine, but we'll just keep plodding along.”